Emancipation

The destruction of slavery powerfully shaped the course of the Civil War and the debate over Reconstruction. The Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 infused the Union war effort with a new moral spirit, and ensured that Northern victory would produce a social revolution in the South. Two years later, Congress enacted and the states ratified the Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery throughout the nation.

Although the Lincoln administration at first insisted that the preservation of the Union, not the abolition of slavery, was its objective, slaves quickly seized the opportunity to strike for their freedom.

As the Union army occupied Southern territory, slaves by the thousands abandoned the plantations. Their actions forced a reluctant Lincoln administration down the road to emancipation.

|

|

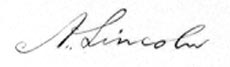

The disintegration of slavery was one among several considerations that led President Lincoln, on January 1, 1863, to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. Lack

of military success, pressure from antislavery Northerners, the

need to forestall British recognition of the Confederacy, and

the desire to tap Southern black manpower for the Union army also

contributed to the decision. |

Copyright

2003