|

Back to The

Calhoun Industrial School Exhibit

Ellis, R. H. (1984). The Calhoun

School, Miss Charlotte Thorn's "Lighthouse on the Hill"

in Lowndes County, Alabama. The Alabama Review, 37(3),

183-201.

Reprinted with permission from

by The Alabama Review (http://www.auburn.edu/~bamarev/),

copyright July, 1994, by the University of Alabama Press (http://www.uapress.ua.edu/).

All rights reserved.

At the close of the Civil War

the primary ambition of the slaves, to be free, had been fulfilled.

They then set about obtaining freedom's corollary, education,

which they believed would give them equality with white men. Blacks

considered labor the bond that had fettered them during the years

of slavery and education the key that would free them from this

bond forever.1 Booker T. Washington declared

that blacks had been "compelled to work for two hundred fifty

years, and now they wanted their children to go to school so that

they might be free and live like the white folks-without working."2

Although this viewpoint might appear somewhat exaggerated, the

zeal with which emancipated blacks pursued education was very

real indeed.

Unfortunately, little money existed

in the post-Civil War South for education. Compounding the financial

problem were the opposition to free schools for either race, the

racial prejudice heated by emancipation, and the necessity of

a dual school system to serve a widely scattered populations circumstance

nearly doubling the cost to the taxpayers (of whom 90 percent

were white). Small wonder that the south accomplished little to

alleviate black illiteracy.

Northern concern for blacks did

not end with emancipation. Sponsored by churches, benevolent societies,

and government agencies, many individuals came South to assist

in the adjustment from slavery to freedom. In spite of their good

intentions these educators found their classical approach to education

unsuited to the needs of the freedmen. Southerners, meanwhile,

declared that the blacks were being indoctrinated, not educated.

Caught in the midst of these disagreements, blacks remained largely

illiterate.

Prior to the war, slaves had been

a unit in Southern agricultural society. Although their servile

position was an unnatural and undesirable one, work and contact

with the whites, however limited, trained blacks not only in agriculture

but also in basic domestic arts, in proper health habits, and

in working as part of a nearly self-sufficient household. The

Civil War and Reconstruction eras ended this training, and freedom

evolved into yet another form of slavery.

However, one approach to black

education offered encouragement: the industrial school, promoted

by General Samuel C. Armstrong and epitomized in Hampton Institute

located in Virginia. At the war's end Armstrong became responsible

for some ten thousand freed slaves camped near Hampton, Virginia,

in hopeless poverty and disorganization. He worked vigorously

to create order out of this chaos and found that the methods that

his father had used as a missionary to the natives of Hawaii could

become the core of a program of manual and agricultural training.

He stressed the moral and spiritual content of all work, even

the simplest task, and the building of character through work,

the making of a life rather than a living. He believed that only

through the training of the whole man-mind, body, and soul-could

the individual successfully be integrated into society.3 In addition, Armstrong saw industrial education as a means

of bettering race relations. Differences between whites and blacks

would change slowly over a long period of time, but he believed

that as soon as Southern white men understood that "an educated

skilled Negro workman was of more value to the community than

an ignorant, shiftless one, the southern white man would take

an interest in the education of the black."4 As Armstrong saw the solution, black youths should be educated

who could

teach and lead their people, first

by example, by getting land and homes; to give them not a dollar

that they could earn for themselves; to teach respect for labor,

to replace stupid drudgery with skilled hands, and to those ends

to build up an industrial system for the sake not only of self-support

and intelligent labor, but also for the sake of character.5

Armstrong's most famous pupil

was Booker T. Washington, founder of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

Both men believed that work developed character as well as habits

of industry.6 Others under Armstrong's charismatic

influence were also convinced of the merit of industrial education

in aiding freedmen. Such a one was Charlotte R. Thorn, an attractive

Yankee socialite from New Haven, Connecticut, who, at the age

of thirty-five, founded the Calhoun School in Lowndes County,

Alabama. Patterned after Hampton Institute, the school demonstrated

that General Armstrong's principles for collegiate education could

be successfully practiced on the high school level, even in the

poverty-stricken backwashes of the Alabama Black Belt.7

As the daughter of a surgeon who

was an officer in the U.S. Navy, Miss Thorn enjoyed all the pleasures

and security associated with a well-to-do, aristocratic family.

Her days were filled with teas, luncheons, and diversions common

to upper-class young ladies during the late 1800s. Attractive

and quick-witted, she was troubled by nothing more serious than

perhaps the decision of which gown to wear or which escort to

accept for a particular dinner party.8

At a gathering in her family's

home in the late 1880s she met General Armstrong. Accustomed to

the usual light party repartee, she was understandably startled

when Armstrong, in the course of their conversation, abruptly

inquired of her, "Do you know you are going to Hampton to

teach Negroes?" Too astounded to do otherwise, she listened

to him. As he told her of the plight of emancipated slaves, he

urged her to utilize her intelligence and training for the benefit

of those less fortunate than she. She laughed at the mention of

her "training" and declared that her greatest accomplishment

to date was playing cards. But evidently Armstrong sensed strength

beneath this intelligent young woman's social veneer. Any attempt

to relate what transpired next would be conjecture, but the next

season found Charlotte Thorn teaching at Hampton Institute.9

|

Charlotte

Thorn (W.N. Hartshorn, ed.,

An Era of Progress and Promise 1863-1910

[Boston, 1910], 334, Hampton Institute, Hampton, Virginia)

|

There she met and became close

friends with another teacher, Mabel W. Dillingham. They had similar

tastes and enjoyed a very pleasant life, but their introduction

to Booker T. Washington on a visit to Hampton changed their lives.

His description of the tragic plight of Alabama blacks anxious

for an education for their children so touched the two women that

they sat up late in the night talking.10 The

next day they informed Washington that they wanted to go to Alabama

to teach and asked him to help them to find a place where the

people were most in need. On his return to Tuskegee he considered

what would be the best location for their work and chose the town

of Calhoun in Lowndes County in the heart of the Alabama Black

Belt. Upon receiving a letter informing them of his choice the

ladies enthusiastically began their preparations.11

In addition to the fact that Lowndes

County had the largest proportion of blacks to whites of any Alabama

county, other reasons pointed to this site. Concerned black men

and women near Calhoun had been meeting regularly to pray that

someone would come there and start a school.12

Calhoun was also a wise choice in Lowndes County because the nearby

railroad offered accessibility to a rural area where roads were

few, unpaved, and hilly-dusty in summer and precipitously slippery

in winter.

Probably it was Mabel Dillingham

who forged ahead in the plan to found the school at Calhoun. Hollis

B. Frissell, the successor to General Armstrong as Hampton's president,

wrote to Booker T. Washington describing Miss Dillingham as "pushing

ahead in her usual enthusiastic way" in her work in Alabama.

Although Frissell did not wish "to throw cold water upon

her plans," he worriedly asked Washington who was directing

Dillingham's work, for "she must have some one who will look

at things more coolly than she is likely to do.... Patient endurance

needs to be cultivated by her."13

October 1892 found the two young

teachers in the midst of three hundred blacks who had come to

the old Ramah Church near Calhoun. Because the church sat in an

isolated area with no road to it, people had walked or ridden

in carts or mule wagons to hear what the white women had to say

about starting a school. Cold weather required the wearing of

"right smart o' clo's" for all, declared one woman who

wore three sunbonnets and two turbans, all the headgear in her

family. Among those present was a seventeen-year-old girl who

taught at the only school in the neighborhood. A young man from

three miles away brought his entire student body; he planned to

close his school and attend the new school along with his pupils.

A Tuskegee graduate introduced the ladies who explained their

plan. At the first meeting approximately two hundred and fifty

dollars cash was raised. The group was emphatic in its distrust

of banks, suggesting instead that the money be trusted to Booker

T. Washington.14 The ladies dreaded asking that

all students pay tuition, for money was extremely scarce; moreover,

the community had thought the school would be free once they raised

the money to build it. However, Washington had emphasized to the

ladies the value of tuition in encouraging industry; he did not

believe in giving something for nothing. Twenty-five, thirty-five,

and fifty cents a month were set as tuition, according to grade

level. One man remarked in an injured tone that he had thought

his child would be worth more than fifty cents. "There is

no charity in giving" became an integral part of the Calhoun

School's philosophy.15

|

|

|

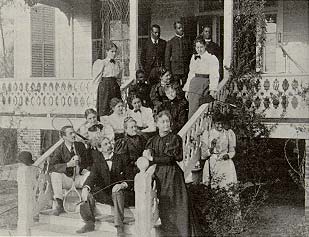

Students of the Calhoun

School

(Hampton Institute Archives, Hampton, Virginia)

|

A board composed of prominent

Northern businessmen and leading educators was formed, and outside

supporting groups sought, because the expenses would far exceed

the modest contributions of the community. The school was quite

successful in attracting financial support from national philanthropic

funds. Doubtless, Booker T. Washington influenced their grant

from the Slater Fund, whose administrator was J. L. M. Curry,

a Montgomerian, who believed that capital followed the schoolhouse.16 Support also came from the General Education Board, distributor

of Rockefeller monies; the Westchester Association; the Frothingham

Fund; and the New Haven Calhoun Fund, probably organized by hometown

supporters of Miss Thorn. However, contributions were not limited

to large philanthropic organizations. Many friends of Hampton

Institute heard of Calhoun's needs through Hampton's official

voice, The Southern Workman, and sent contributions. School reports

also listed contribution from churches of various denominations,

Sunday School classes, missionary societies, women's clubs, civic

groups, and individuals from all walks of life.17 Nor were all contributors from the North. A Southern landowner,

N. J. Bell of Montgomery, made perhaps the most significant donation,

the initial ten acres of land that the founders had selected as

the site for their school.18 Several years later

Booker T. Washington recalled the selection of that site. It had

been raining, and it rained harder and harder. After quite a wait

Miss Dillingham suggested that the group provide for themselves

in the best way possible against the wet weather and go outside.

"I see her now," he remembered, "as she stood with

an umbrella over her head and with the mud up to her ankles, while

we decided upon the exact spot and measured off the ground where

the first building was to be."19

The task before the women was

awesome. Few whites spoke to or associated with the teachers,

because they worked with blacks. Even the poorest whites ignored

them and looked the other way when they passed. When the teachers'

trunks and supplies arrived at the Calhoun railroad station, the

townspeople could not understand why women of obvious refinement,

judging from the piano and the tasteful, solid pieces of furniture,

would voluntarily choose a life spent among blacks in the most

backward part of a most backward county.20

The ladies did not consider themselves

martyrs, however, and they asked for no sympathy. "Their

pluck," one newspaper reported, was matched "by their

good humor." They laughed when they heard that local whites

speculated that they had run away from their husbands and hoped

to gain anonymity in the Black Belt.21 Although

the white community as a whole ignored the newcomers, the teachers

were not totally without white friends. The Smiths, the Dickeys,

the Bells, and the Chestnuts, as well as others provided invaluable

advice on how to build, plant, harvest, and adapt in this environment

so different from New England.22

Miss Thorn intended that the first

building, the teachers' cottage, be a model in the community.

This simple dwelling utilized natural materials available to any

in the locality who wished to imitate it. Inside were flowers,

pictures, and bright covers for the furniture, designed as object

lessons in "home adornment." All who might wish to walk

through the cottage at any time were welcomed. Many blacks toured

the building, although many seemed strangely reluctant to go upstairs,

perhaps because they were accustomed to one-story cabins.23

Construction of' schoolhouses, barns, shops, and dormitories soon

followed completion of the teachers' cottage, and the cluster

of white buildings came to be known as "The Lighthouse on

the Hill." Many of the older blacks called it "De Mornin'

Star."24

The teachers sought to enhance,

not to replace, the pattern of life around them. They built with

native materials, taught skills needed in everyday work and life,

planted shrubs from the surrounding woods on the campus (seventeen

varieties of native trees and shrubs are still to be seen on the

campus today), and as quickly as possible utilized graduates as

assistants. After completion of higher education at Hampton, many

Calhoun graduates returned home as instructors. Building developed

carpentry skills; painting was an "applied science."

A dairy served the needs of the school, trained young men as they

cared for the animals, and became a pattern for other schools.

Each student received a thorough grounding in educational basics;

vocational skills supplemented but did not supplant instruction

in reading, writing, arithmetic, history, and the appreciation

of literature. As the campus expanded, so did Calhoun's reputation

as a model industrial school.25

Although the Hampton plan was

the pattern for the Lowndes County school's program, the community's

needs dictated some of Calhoun's activities. At the first meeting

with the white teachers the older men had declared that they,

too, wanted the chance to learn. The school responded with a program

of adult education at night with two teachers conducting classes

four evenings a week. At this time an educational program for

the community in conjunction with a high school curriculum was

unusual, if not unique.26

By far the most noteworthy innovation

among the school's many community projects was the program to

encourage black sharecroppers to purchase land. Thomas B. Patterson,

a Hampton graduate who also trained boys in farm work, believed

that the major reason farmers did not cultivate land more carefully

was because they did not own it and feared that any improvements

would raise their rent.27 The school organized

a land bank to provide land for purchase. The core of the land

offered for sale to tenants had earlier been secured reputedly

for experimentation by Tuskegee's famous scientist, Dr. George

Washington Carver. When that experiment did not materialize, plans

were made to utilize the property for individual farms, and in

1894 a land company was organized. Eventually, the land bank contained

over 4,081 acres. This property was then sold in forty- to sixty-acre

tracts, with some ten-acre plots sold to women. Northern friends

of the school financed the purchases at 8 percent interest.28

In addition to improved farming methods, blacks learned to raise

food crops first (to prevent indebtedness to merchants) and a

money crop such as cotton second (to be used for land payment).

In three years one could buy a thirty-acre tract, as land sold

for five to ten dollars an acre. The cost was equivalent to renting

a farm for $ 100 a year. One Calhoun teacher reported that to

blacks the promise of landownership as a means of salvation stood

next to the discovery of the "Bible as a book of righteousness

versus voodooism. Land-owning, or the chance to own, seems to

give instant and regenerating interest to a stagnant life. It

pulls the individual together for a struggle which means self-help,

self-control and a consequent self-respect."29

Thus, the landownership program epitomized the Calhoun School's

philosophy. In the first thirteen years $36,100 was paid on notes,

with ninety-two deeds issued to eighty-five persons. These new

landowners built for themselves houses of three to eight rooms,

distinct improvements over the customary one-room sharecropper

cabins. Even more important than the physical improvements in

houses and land was the improved quality of the people's lives,

as they learned that "the only freedom in life is to owe

no man anything."30

One former Calhoun student recalled

how both her father and grandfather bought land from the school.

Consequently, as a member of a concerned family she was sent to

Calhoun from kindergarten through high school, where she learned

cooking and sewing in addition to the basic academic skills. Her

family filled their summers with gardening and canning, all as

a part of the total program that bound school and community together.31

The school also influenced the

community through promotion of better health care. Since Miss

Thorn's father had been a surgeon in the U.S. Navy, she was particularly

aware of the dangers that accompanied carelessness about cleanliness

in treating disease. Whenever she could, she treated the sick

herself.32 A program of community health care

became an integral part of the school's activities. The school

nurse visited the sick whenever possible. Over 280 children were

examined for hookworm, with ten cases found and cured, and one

senior student remarked that before the hookworm treatment he

had never known what it was to feel really well. Students were

fitted for glasses, checked for diphtheria, and relieved of diseased

tonsils; they ate balanced meals in the boarding school or bought

nourishing sandwiches for a penny. 33

In addition to the adult education

classes, landownership program, medical outreach, Miss Thorn instituted

monthly parents' meetings, farmers' conferences, and homemaking

clubs. The faculty visited in neighboring churches, homes, and

schools, and Calhoun graduates supervised by Calhoun's head teacher

directed two outpost schools at Sandy Ridge and Lee Place. 34

Amusements were not neglected;

the school sponsored community Thanksgiving and Christmas programs,

plus other informal meetings with refreshments and outdoor games.

One Calhoun resident recalled that Miss Thorn organized Christmas

parties especially for the local white children; she strove not

to overlook any part of the community.35 Another

Calhoun resident reminisced that on Christmas morning older boys

from the school serenaded area residents. "I recall Mama

fixing up a box of cakes for them as they came around, as far

back as I can remember."36

Miss Thorn sought to meet the

needs of the people, simultaneously elevating their character,

always stressing standards of excellence, whether in deportment

or in domestic work. A longtime resident of Fort Deposit remembered

that the town's white women always preferred Calhoun trainees

to do their ironing, because Miss Thorn's students were such perfectionists.37

One Calhoun graduate recalled how Miss Thorn was never too busy

to notice the behavior of the students, being often in their midst

before they were aware of her presence. Afflicted with an undetermined

illness, she walked with crutches for years. With her crutches

and black clothes she was respectfully referred to as "creepin'

jesus." Miss Thorn, worried that the conduct of the local

blacks on Saturdays might tempt her students, firmly changed the

school week to run from Tuesday through Saturday. However, a play

session at the school on Saturday afternoons compensated for the

day's fellowship lost in town.38

One of the most practical contributions

of the school to the community was the promotion of better roads.

The terrain surrounding Calhoun made access difficult, because

many of the hills were faced with a slippery mud locally known

as "blue marl." Consequently, when the small farmer

did produce a valuable crop, he faced the worry and expense of

getting it to market. There was a railroad, but its freight charges,

while not unreasonable to large planters, proved prohibitive to

the small farmers. Not until forty years after the school opened

was the formidable problem of engineering and financing a road

through the clay-faced hills totally solved. Miss Thorn's nephew,

Thorn Dickinson, a graduate of Williams College and Massachusetts

Institute of Technology, laid out the stretch of road that connected

Calhoun with the outside world (today identified on maps as Lowndes

County 33, from Calhoun to Alabama Highway 21). The road was a

joint venture between the school and the county, with the school

grading it and the county surfacing it with gravel.39

Calhoun's founders consistently

attempted to link the school and community. Doubtless, the keystone

of this industrial plan secondary school was its staff, for they

were the epitome of dedication. From its beginning under two white

Yankee schoolteachers and their black counterpart, Miss Georgia

Washington, the school's ideas and ideals were personified by

those who directed it. The successors to the founders at Calhoun

were not misfits or persons escaping from their past lives. Rather,

they appear to have been intelligent, educated, dedicated men

and women who genuinely wanted to improve the lives of the impoverished

blacks. One 1937 account of the school in the Birmingham Age-Herald

noted that the staff included graduates of Yale University, Williams

College, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, while a Harvard

graduate was principal. 40

|

|

|

The Staff of the Calhoun

School

(Hampton Institute Archives, Hampton, Virginia)

|

Despite Calhoun's outstanding

staff and successful program more people outside Alabama than

within the state were aware of the scope and nature of the Calhoun

School's work. 41 The school's guest book reflects

the interest that Calhoun's success stimulated in institutional

circles, educational and otherwise. Among those who came to observe

the school's facilities and methods were educators from China,

Japan, Ceylon, Scotland, England, Poland, Korea, and various countries

in Africa. Visitors also included Y. M. C. A. personnel, prospective

missionaries, and an Illinois state prison warden.42

The school's reputation received

national recognition in 1917 when a nationally known sociologist

cited the Calhoun School as highly effective in character development,

using industrial and agricultural training fitted to the needs

of the community. The staff of twenty-seven included twelve whites,

fifteen blacks, all of whom had graduated from reputable schools

and were now devoted to their work. The sociologist's report stressed

Calhoun's standards of excellence in all phases of its program,

whether home training for the boarding school girls, well-kept

buildings and grounds, or exactness in the keeping of the school's

financial records. The organization and management of the land-purchasing

companies, which had then bought and resold to small farmers approximately

4,000 acres of land, was noted as particularly impressive.43

Fifteen years later, in 1932,

Charlotte Thorn, Calhoun's principal of more than forty years,

died at age seventy-five. She left as her memorial a model industrial

school for blacks. But a living memorial of Calhoun graduates

surpassed the school per se. Calhoun graduates were always encouraged

to gain as much education and experience as possible before returning

to Lowndes County to strengthen the black community by joining

the staff in various capacities or by establishing homes that

contributed to the upgrading of the community through the participation

in church and civic activities.

For some years before Miss Thorn's

death the school had grown weaker, and after years of only survival

existence Calhoun's trustees agreed in 1943 to deed the school

property to the state of Alabama and to give the Lowndes County

Board of Education responsibility for supervising

Calhoun as a public school.44 Today it operates

as a typical rural public school in Alabama's Black Belt.

The demise of Calhoun as a private

industrial school cannot be attributed to any one cause. One Calhoun

resident believes the decline began when the school's graduates

found economic and social opportunities outside Lowndes County

and failed to return and to enrich both the school and the community.45

Certainly, in the years immediately after the turn of the century

the small farmer's lot steadily deteriorated, until supporting

a family on forty to sixty acres, no matter how frugal one might

be, became almost impossible. In a sense, then, the community

of independent small farms on which Miss Thorn based her school's

curriculum was doomed to extinction even as the Calhoun program

nurtured it. Too, the economic depression of the 1930s depleted

the resources of many contributors to the school, some of whom

had already begun to withdraw their support as public education

gained momentum. Still others among the early supporters had died.

In 1975 a historian assigned to

prepare a history and evaluation of the school for the National

Register of Historic Places pronounced the school doomed because

its curriculum failed to provide full educational opportunity

for blacks. He further stated that its program of community work

was no substitute for social, economic, and political equality.46 Whatever degree of accuracy this judgment contained, it

is equally as true that the school fulfilled a need in that place

and at that time when no other program could have met the needs

and assured the survival, much less the progress, of a needy people.

Finally, it is certain that the

death of Miss Thorn adversely affected the school. Although her

successors strove to emulate her standards and spirit, it was

she who had single-mindedly directed its program of industrial

education toward the goal of enriching the lives-physically, mentally,

socially, and spiritually-of the black people in Lowndes County.

And in accomplishing her purpose she demonstrated that the industrial

school of education was as feasible on the primary and secondary

levels as it was on the college level. Indeed, schools such as

Calhoun proved to be especially effective instruments to improve

the standard of living and the quality of life among emancipated

blacks in the post-Civil War South.

References:

| 1

|

Charles

William Dabney, Universal Education in the South (2

vols., Chapel Hill, 1936), I, 447. |

| 2 |

Booker

T. Washington, My Larger Education (Garden City, N.Y., 1911),

21-35, in Lucille Griffith, Alabama: A Documentary History

to 1900 (University, Ala., 1968), 571. |

| 3 |

Dabney,

Universal Education, 98. |

| 4 |

Edith

Armstrong Talbot, Samuel Chapman Armstrong: A Biographical

Study (New York, 1904), 208. |

| 5 |

Ibid.,

157. |

| 6 |

Dabney,

Universal Education, 499. The definitive biography

of Booker T. Washington is Louis R. Harlan, Booker T. Washington:

The Making of a Black Leader, 1856-1901 (New York, 1972),

and Booker T. Washington: The Wizard of Tuskegee, 1901-1915

(New York, 1983). |

| 7 |

For

a brief discussion of the Calhoun School see Robert G. Sherer,

Subordination or Liberation? The Development and Conflicting

Theories of Black Education in Nineteenth Century Alabama

(University, Ala., 1977), 68-69, 171 n. 12 and n. 14, and

Glenn Nolan Sisk, "Alabama Black Belt: A Social History,

1875-1917" (Ph.D. dissertation, Duke University, 1951),

191-92. |

| 8 |

Dabney,

Universal Education, 88. |

| 9 |

Ibid. |

| 10 |

Ibid. |

| 11 |

Louis

R. Harlan, ed., The Booker T. Washington Papers (12

vols., Urbana, 1974-1982), III, 481. |

| 12 |

Dabney,

Universal Education, 487. |

| 13 |

Harlan,

Washington Papers, III, 161-62. |

| 14 |

Hampton

Evening Post, March 7, 1892. |

| 15 |

Chicago

Sunday Inter-Ocean, March 12, 1893, Manuscript Collection, The

Calhoun School, Calhoun. |

| 16 |

A

Harvard graduate and classmate of Rutherford B. Hayes, Curry

served in the Alabama legislature, the Confederate Congress,

and the Confederate army. After the war he was most noted

as the chief administrator first of the Slater Fund and later

of the Peabody Fund, both major contributors to postwar Southern

educational programs. Curry's insistence that only schools

with industrial training departments receive these funds reflected

his commitment to industrial education. Horace Mann Bond,

Negro Education in Alabama: A Study in Cotton and Steel

(New York, 1939), 202; Thomas McAdory Owen, History of

Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography (4 vols.,

Chicago, 1921), III, 444-45. |

| 17 |

The

Calhoun School, pamphlet (Montgomery, n.d.), Lowndes County

Folder, Alabama State Department of Archives and History,

Montgomery. |

| 18 |

Montgomery

Advertiser, March 11, 1976. |

| 19 |

Harlan,

Washington Papers, 111, 482-83. |

| 20 |

Chicago

Sunday Inter-Ocean, March 12, 1893. |

| 21 |

Ibid. |

| 22 |

Dabney,

Universal Education, 487-88; Southern Workman,

XLIII (August 1914); personal interview with Rogers Smith

in Calhoun, July 29, 1982. |

| 23 |

Chicago

Sunday Inter-Ocean, March 12, 1893. |

| 24 |

Dabney,

Universal Education, 487-88; Southern Workman,

XLIII (August 1914); personal interview with Rogers Smith

in Calhoun, July 29, 1982. |

| 25 |

Southern

Workman, XLIII (August 1914). |

| 26 |

Hampton

Evening Post, March 7, 1892. |

| 27 |

Harlan,

Washington Papers, III, 438-39; Southern Workman, XII

(January and March 1893). |

| 28 |

W.

N. Hartshorn, ed., An Era of Progress and Promise, 1863-1910

... (Boston, 1910), 337; Dabney, Universal Education,

487; William L. McDavid, "Calhoun Land Trust: A Study

of Rural Resettlement in Lowndes County, Alabama" (M.A.

thesis, Fisk University, 1943). |

| 29 |

Pitt

Dillingham, "Land Tenure Among the Negroes," Yale

Review, V (August 1896), 204-06. |

| 30 |

Hartshorn,

Era of Progress and Promise, 337. |

| 31 |

Personal

interview with Lee Taylor in Calhoun, August 7, 1982. |

| 32 |

Dabney, Universal Education, 488. |

| 33 |

The

Calhoun School, pamphlet (Montgomery, n.d.), Manuscript Collection,

The Calhoun School, Calhoun. |

| 34 |

The

Calhoun Colored School, pamphlet (Montgomery, n.d., earlier than above),

personal collection of Joseph Cates, Ft. Deposit. |

| 35 |

Personal

interview with Willis Dickey in Calhoun, August 15, 1982. |

| 36 |

Personal

interview with Rogers Smith in Calhoun, July 29, 1982. |

| 37 |

Confidential

personal interview in Ft. Deposit, July 2, 1982. |

| 38 |

Personal

interview with Ethel Zeigler in Calhoun, August 7, 1982. |

| 39 |

Personal

interview with Rogers Smith in Calhoun, July 29, 1982. |

| 40 |

Birmingham

Age-Herald, January 19, 1937. |

| 41 |

Ibid. |

| 42 |

Calhoun

School Guest Book, Manuscript Collection, The Calhoun School,

Calhoun; Montgomery Advertiser, March 11, 1976. |

| 43 |

Thomas

Jesse Jones, ed., Negro Education: A Study of the Private

and Higher Schools for Colored People in the United States,

Bureau of Education Bulletin No. 38, 1916 (2 vols., Washington,

D.C., 1917), 11, 58-59. |

| 44 |

James

Sheire to Milo B. Howard, Jr., May 22, 1975, The Calhoun Colored

School: Nomination Form for National Register of Historic

Places, Lowndes County Folder, Alabama State Department of

Archives and History, Montgomery. |

| 45 |

Personal

interview with Rogers Smith in Calhoun, July 29, 1982. |

| 46 |

James

Sheire to Milo B. Howard, Jr., May 22, 1975. |

Citation for this article:

Ellis, R. H. (1984). The Calhoun School, Miss Charlotte Thorn's

"Lighthouse on the Hill" in Lowndes County, Alabama. The

Alabama Review, 37(3), 183-201.

Reprinted with permission from

by The Alabama Review (http://www.auburn.edu/~bamarev/),

copyright July, 1994, by the University of Alabama Press (http://www.uapress.ua.edu/). All rights

reserved.

|

|