Biographical

Sidebar:

Albion W. Tourgée

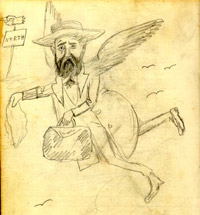

William Sydney Porter, the famous short story writer whose pseudonym was O. Henry, drew this humorous sketch of Tourgee. Courtesy of the Greensboro Public Library/Greensboro Historical Museum |

Throughout his long career, carpetbagger Albion W. Tourgée (1838-1905) advocated equal rights for African-Americans. Born on an Ohio farm, he attended the University of Rochester before serving in the Union army. He was twice wounded, and spent four months in Confederate prisons. After the war, Tourgée moved with his wife to North Carolina, where he became involved in Reconstruction politics. At the constitutional convention of 1868, he was instrumental in democratizing the state's local government and judicial system. |

A

lawyer, Tourgée served as a Superior Court judge from 1868 to 1874.

As a member of the northern branch of the Methodist Episcopal Church,

he helped organize the school which became Bennett College.

As a superior

court judge during Reconstruction, Tourgée courageously challenged

the Ku Klux Klan. His appeals to Congress revealing the extent of violence

helped speed passage of laws authorizing the use of troops against the

Klan.

![]() Learn

more about Tourgée's viewpoint on the KKK

Learn

more about Tourgée's viewpoint on the KKK

In 1896, Tourgée served without fee as attorney for Homer A. Plessy, who challenged a Louisiana law requiring the racial segregation of railroad cars. By denying blacks equal protection of the law, Tourgée argued, segregation violated the Fourteenth Amendment. Telling the court that “probably most white persons would prefer death to life in the United States as colored persons,” he said that the Constitution should be “color blind.”

In Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court upheld the law and announced the principle of "separate but equal." Not until 1954, in the Brown school segregation decision, did the Court adopt Tourgée's earlier reasoning.