|

Negro

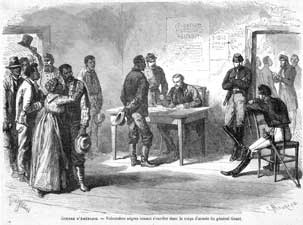

Volunteers enrolling in Gen. Grant's Army Corps, engraving

from Le Monde Illustre, 1863

|

| |

From

the beginning of the war, Northern African-Americans volunteered

for service, and escaping Southern slaves offered to fight for

the Union. Northerners at first feared that white soldiers would

not fight alongside black.

Not

until 1863, with white enlistment lagging and emancipation now

a war aim, did black recruitment begin in earnest. By the end

of the war, some 200,000 black men, the large majority former

slaves, had served in the Union army and navy. Many hailed from

loyal border states like Kentucky - excluded from the Emancipation

Proclamation - where military service remained for most of the

war the only legal route to freedom.

Within

the army African-Americans were anything but equal to white

soldiers. Serving in segregated units, black recruits were initially

paid less (an inequity corrected by Congress in 1865) and were

assigned mainly to fatigue duty, construction work, and menial

labor.

On the battlefield they were brave and effective soldiers against

an enemy that could be particularly hostile to them. If captured

by Confederate forces, they faced the prospect of summary execution

(as occurred at the Fort Pillow Massacre of 1864) or sale into

slavery. Yet even after proving themselves in battle, they did

not advance into the ranks of commissioned officers until late

in the war.

By

playing a central role in winning the war, black soldiers staked

a claim to equal rights in the postwar republic. "Once

let the black man get upon his person the brass letters U.S.,"

wrote Frederick Douglass, who crisscrossed the North recruiting

black volunteers, "and there is no power on earth which

can deny that he had earned the right to citizenship."

Image

25 of 77

Image

25 of 77