|

Jacob

Riis

A

Danish immigrant, Jacob Riis was the pioneer in the use photography

as an instrument of reform. A crusading newspaper reporter who

took his camera into urban slums.

Riis

gained lasting recognition as a result of a book entitled How

the Other Half Lives. In the past, he wrote, “the half that

was on top cared little for the struggles, and less for the fate

of those who were underneath.” But he wanted to rectify

that omission.

Reading

Riis’s book today can be a disturbing experience. His book

is filled with condescending and insulting generalizations. Italian

immigrantss were “content to live in a pig-sty.” Chinese

immigrants were “in no sense a desirable element of the

population. For Eastern European Jews, he wrote, “Money

is their God. Life itself is of little value compared with even

the leanest bank account.” About African Americans, he wrote,

“Poverty, abuse and injustice alike the Negro accepts with

imperturbable cheerfulness.”

Take

a look at the following Riis photographs and read selections

from Jacob Riis' book, How the Other Half Lives, 1889.

|

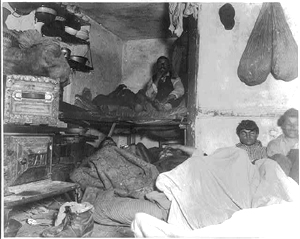

In a room not thirteen feet either

way slept twelve men and women, two or three in bunks set

in a sort of alcove, the rest on the floor. A kerosene lamp

burned dimly in the fearful atmosphere, probably to guide

other and later arrivals to their beds, for it was only just

past midnight.

A baby’s fretful wail came from an adjoining

hall-room, where, in the semi-darkness, three recumbent

figures could be made out. The apartment was one of three

in two

adjoining buildings we had found, within half an hour,

similarly crowded. Most of the men were lodgers, who slept

there for

five cents a spot. |

| Unauthorized immigration lodgings in a Bayard St. N.Y.C.

tenement, ca. 1890 |

| The twenty-five cent

lodging-house keeps up the pretence of a bedroom, though

the head-high

partition enclosing a

space just large enough to hold a cot and a chair and allow

the man room to pull off his clothes is the shallowest of

all pretenses. The fifteen-cent bed stands boldly forth without

screen in a room full of bunks with sheets as yellow and

blankets as foul. At the ten-cent level the locker for the

sleeper's clothes disappears. There is no longer need of

it. The tramp limit is reached, and there is nothing to

lock up save, on general principles, the lodger. Usually

the ten- and seven cent lodgings are different grades of

the same abomination. Some sort of an apology for a bed,

with mattress and blanket, represents the aristocratic purchase

of the tramp who, by a lucky stroke of beggary, has exchanged

the chance of an empty box or ash-barrel for shelter on the

quality floor of one of these "hotels." |

|

|

I have not forgotten the deputation of

ragamuffins from a Mulberry Street alley that knocked at

my office door one morning on a mysterious expedition for

flowers, not for themselves, but for "a lady," and

having obtained what they wanted, trooped off to bestow

them, a ragged and dirty little band, with a solemnity

that was quite unusual.

It was not until an old man called the next day to thank

me for the flowers that I found out they had decked the

bier of a pauper, in the dark rear room where she lay waiting

in her pine-board coffin for the city's hearse.

Yet, as

I knew, that dismal alley with its bare brick walls,

between which no sun ever rose or set, was the world of

those children.

It filled their young lives. Probably not one of them

had ever been out of the sight of it. |

| Three children huddle for warmth in window well on NY's

Lower East Side |

|

|

The years have brought to the

old houses unhonored age, a querulous second childhood that

is out of tune with

the time, their tenants, the neighbors, and cries out against

them and against you in fretful protest in every step on

their rotten floors or squeaky stairs.

Good cause have they

for their fretting. This one, with its shabby front and

poorly patched roof, what glowing firesides, what happy

children

may it once have owned? Heavy feet, too often with unsteady

step, for the pot-house is next door--where is it not

next door in these slums?--have worn away the brown-stone

steps

since; the broken columns at the door have rotted away

at the base.

Of the handsome cornice barely a trace is left.

Dirt and desolation reign in the wide hallway, and danger

lurks on the stairs. Rough pine boards fence off the

roomy fire-places--where coal is bought by the pail at

the rate

of twelve dollars a ton these have no place. The arched

gateway leads no longer to a shady bower on the banks of

the rushing

stream, inviting to day-dreams with its gentle repose,

but to a dark and nameless alley, shut in by high brick

walls,

cheerless as the lives of those they shelter. |

| Bandit’s

Roost, c. 1888 |

| The wolf knocks loudly at the gate in the troubled

dreams that come to this alley, echoes of the day's cares.

A horde of dirty children play about the dripping hydrant,

the only thing in the alley that thinks enough of its chance

to make the most of it: it is the best it can do. These are

the children of the tenements, the growing generation of

the slums; this their home. From the great highway overhead,

along which throbs the life-tide of two great cities, one

might drop a pebble into half a dozen such alleys. |

|

| |

|

| Home

of an Italian Ragpicker, 1888 |

|

|