|

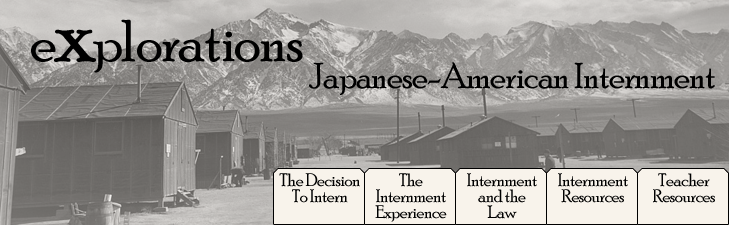

Image information: Manzanar street scene, clouds, Manzanar Relocation Center, California, photograph by Ansel Adams, digital file from original print http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppprs.00284

Japanese-American

Internment

During

World War II, the federal government ordered 120,000 Japanese-Americans

who lived on the West coast to leave their homes and live in 10

large relocation camps (see Internment

Map) in remote, desolate areas, surrounded by barbed wire

and armed guards. Two-thirds were native-born American citizens.

|

Evacuation

sale during Japanese Relocation. FDR Library. |

Japanese-Americans

were interned as a result of an executive order (see Executive

Order No. 9066) by President Roosevelt in 1942. About 77,000

American citizens and 43,000 legal and illegal resident aliens

were affected by the order. The last camp was closed in January

1946, five months after World War II ended.

It

would not be until 1988 that the U.S. government formally apologized,

provided compensation to those who were interned, and created

an education fund to preserve the history and to teach the lessons

of this shameful episode. (see Redress

for Japanese Internees)

|

Two

of the chief backers of a national apology had themselves

been interned. Representative Robert Matsui of California

was 6 months old when his family was interned.

His

family had just 48 hours to relocate. His father was forced

to sell their house in Sacramento for $50 and simply abandon

his small produce business. |

Learn

more about Robert Matsui and the internment of his family

at Tule Lake Camp. (see Recalling the

U.S. Internment of the Japanese With Congressman Robert

Matsui, John F. Kennedy Library and Foundation Responding

To Terrorism Series, November 4, 2001) Learn

more about Robert Matsui and the internment of his family

at Tule Lake Camp. (see Recalling the

U.S. Internment of the Japanese With Congressman Robert

Matsui, John F. Kennedy Library and Foundation Responding

To Terrorism Series, November 4, 2001) |

U.S.

Secretary of Transportation Norman Mineta of California

was ten years old; he and his family were forced to live,

at first, in a converted stables at a racetrack; later,

they spent a year in an internment camp in a forbidding

part of Wyoming.

Mineta

recalled being given the priviledge of signing the House

bill, HR 442, after it had passed. |

|

"There

has never been a moment when I loved this country more,"

he said. Redress was "the best expression of what

this nation can be and the power of government to heal

and make right what was wrong."

Learn

more: Japanese

American National Museum Learn

more: Japanese

American National Museum

|

|

|

Another

sponsor, Democrat Senator Daniel K. Inouye of Hawaii,

who served in the 442nd regiment combat team, made up

entirely of Japanese Americans. He lost his right arm

fighting in Italy and was awarded a Bronze Star and two

Purple Hearts.

Learn

more about the 442d combat team in "21

Asian American World War II Vets to Get Medal of Honor"

He

was first Congressman from Hawaii and the first American

of Japanese descent to serve in either House of Congress. |

Learn

more about Senator Inouye's combat experience during World

War II from his website, Go

For Broke, a condensation of his book, Journey

to Washington. Learn

more about Senator Inouye's combat experience during World

War II from his website, Go

For Broke, a condensation of his book, Journey

to Washington.

|

The

warning radio suddenly emitted a frenzied cry: "This

is no test! Pearl Harbor is being bombed by the Japanese!

I repeat: This is not a test!"

"Papa,"

I cried, and then froze into stunned immobility. Almost

at once my father was in the doorway with agony showing

on his face, listening, caught by that special horror

instantly sensed by all Americans of Japanese descent.

".

. . not a test. We can see the Japanese planes . . ."

|

''Yes,

the nation was then at war, struggling for its survival,'' said

President Ronald Reagan at the White House. ''And it's not for

us today to pass judgment upon those who may have made mistakes

while engaged in that great struggle. Yet we must recognize

that the internment of Japanese-Americans was just that, a mistake.''

More than a mistake, it was a grave violation of civil liberties

and a blot on America’s commitment to constitutional rights.

|

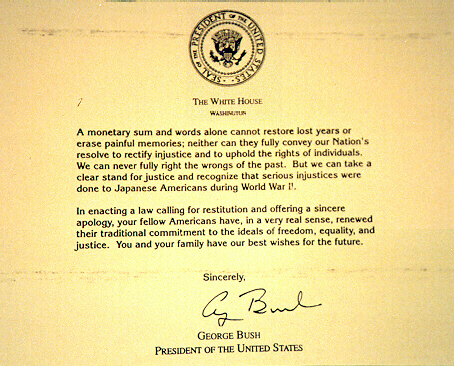

The

Civil Rights Act of 1988 (HR442) awarded redress

to all surviving internees or their relatives.

President George Bush sent this formal apology letter

along with a $20,000 check. |

Exploration

Questions

- Why

were Japanese Americans expelled from their homes and incarcerated

in internment camps - even though not one Japanese American

was charged with espionage or sabotage during the war - and

why did internment last, on average, for nearly three years?

- Why

were west coast Japanese American citizens relocated - while

Japanese Americans in Hawaii and German-Americans and Italian-Americans

were not?

- Why

were all west coast Japanese Americans interned, citizens

and aliens, children and adults, and why was this policy upheld

by the federal courts?

- What

was the impact of this experience upon the lives of Japanese

Americans?

|