|

A

Brief History of Photography

|

The

first photograph was an image recorded on a pewter plate

by a Frenchman, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, in

1826. It showed the view from an upper story window in his

home.

Great

strides in photography would not take place until the

next decades, when Louis Daguerre created images

on silver-plated copper, coated with silver iodide, which

developed with mercury. |

In

daguerreotypes, the images seem to float above the highly

polished silver.

At

first, there was no agreement about what to call the new

process. Among the terms bandied about were No daugerreotype,

crystalotype, talbototype, colotype, crastalograph, panotype,

hyalograth, ambrotype, and hyalotype. Ultimately, a new

word won out - photography, which means writing with

light.

Daugerreotypy

was a cumbersome and time consuming process. The biggest

problem was that it was impossible to duplicate daguerreotypes.

But by the end of the 1850s, the daugerreotype had been

replaced by a new method of photography known as the wet

plate process. A British photographer named Frederick S.

Archer discovered that a glass plate coated with a mixture

of silver salts and an emulsion made of collodion could

record an image. The image had to be developed immediately,

before the emulsion dried. But it was now possible for the

first time to make unlimited prints from a negative. It

was also possible for photographers to take pictures outside

of a studio. |

|

|

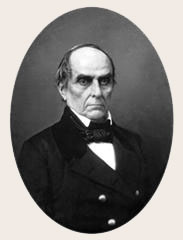

A

key figure in early American photography was Matthew Brady,

who was just 22 years old when he took up photography in

1844. At first, many of his photographs were portraits of

famous Americans, such as Senator Daniel Webster.

These

photographs tended to portray individuals in solemn poses

that reflected the republican emphasis on dignity and

virtue

and made no effort to show the background or setting.

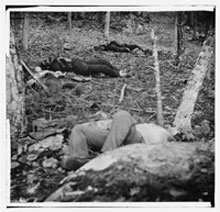

Brady

gained lasting fame for his Civil War photographs,

which have

created lasting images of the conflict in terms of rotting

corpses and raved cities. Yet however lifelike these

pictures

seem, we must realize that they were not accurate depictions

of wartime realities. Photographers like Brady and

Alexander Gardner carefully arranged the scenes, and

even moved corpses to ensure

that they

appeared where

he wanted them.

|

| Senator

Daniel Webster |

During the Civil War period, the process

of taking photographs was complex and time-consuming. Two

photographers would arrive at a location. One would mix

chemicals and pour them on a clean glass plate. After the

chemicals

were given time to evaporate, the glass plate would be

sensitized by being immersed -- in darkness -- in a bath

solution. The

photgrapher would then place the plate in a holder and

insert it in the camera, which had been positioned

and

focused by the

other photographer.

Exposure of the plate and development of the photograph

had to be completed within minutes; then the exposed plate

was

rushed to the darkroom wagon for developing. Each fragile

glass plate had to be treated with great care after development

-- a difficult task on a battlefield. |

Cold

Harbor, Va.Photographer's

wagon and tent (Between 1860 and 1865) Cold

Harbor, Va.Photographer's

wagon and tent (Between 1860 and 1865)

Library of Congress

|

|

|

|

[Gettysburg,

Pa. Four dead soldiers in the woods near Little Round

Top].1863.

Photograph by Alexander Gardner |

[Antietam, Md. Confederate

dead by a fence on the Hagerstown road]. 1862.

Photograph by Alexander Gardner |

[Confederate and Union dead side by side in the trenches

at Fort Mahone]. 1865 |

Selected

Civil War Photographs at the Library of Congress |

In

1885, American inventor George Eastman introduces film made on

a paper base instead of glass, wound in a roll, eliminating the

need for glass plates. Three years later, he introduced the lightweight,

inexpensive Kodak camera, using film wound on rollers. He also

began to develop films in his own processing plants. No longer

did amateur photographers to process their own pictures.

|

|

Some

professional responded to the growth of amateur photography

by attempting to transform the photograph into a work of

art.

One

of the most famous American photographers, Alfred Stieglitz,

experimented with camera angles, close ups,

and focus to created photographs that resemble impressionist

paintings.

Cultural historian Bram Dijkstra wrote that "it

was Stieglitz who... provided the essential example of

the means by which the artist could reach out to a new,

more accurate mode of representing the world of experience." |

|

“Winter on Fifth Avenue”,

1897, photogravure from Picturesque Bits of New York,

1897. |

|

"The Steerage." 1907.

Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz. |

|