|

Teacher

Resources

Jefferson

Defines Indian Policy | Monroe Alters

Direction of Indian Policies | Acculturation

Indian Removal Policy | Resistance

to Indian Removal | The Human Meaning

of Indian Removal

Lesson Plans

Jefferson

Defines Indian Policy

There

is an excellent book related to this topic: Jefferson

and the Indians: The Tragic Fate of the First Americans by

Anthony F. C. Wallace. The website contains information

and resources

that will be helpful in teaching this section.

http://www.hup.harvard.edu/features/waljef/index.html

Back

to Top

Monroe

Alters Direction of Indian Policies

Indian Peace medals were produced by the United States government

and given to Indian leaders in the course of our nation’s

negotiations with the multitude of tribes that owned the

land coveted

by the national and state governments. It is interesting

to study the different designs of these peace medals are

they evolved. Dr. Jack Campisi states:

Nearly every president from George Washington through Benjamin

Harrison had medals issued with his likeness engraved on

the front or obverse side; however, it is the reverse side

that draws our interest. Here was emblazoned in pewter, bronze,

or silver the central justification for our nation’s policy

toward Indian tribes. This policy contrasted a Euro-American

definition of civilization with a perceived Native condition

of savagery. The components of this perception are presented

on the medals in bas relief as bipolar: agriculture versus

hunting, settlement versus nomadism, war versus peace, and

ultimately assimilation versus tribalism.

Meaning in the Reverse: Indian Peace Medals by Dr. Jack

Campisi

http://www.pequotmuseum.org/Home/CrossPaths/CrossPathsWinter20034/

MeaningintheReverseIndianPeaceMedals.htm

Contrast the reverse side of the two medals

below as to the purpose and meaning behind the visual message.

|

|

George Washington Indian Peace

Medal - reverse

Etching of medallion: on recto: Red

Jacket smoking long pipe, George Washington on left

with right hand

extended, below inscription: George Washington / President

/ 1792;

on verso: presidential seal.

Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

|

James Monroe Indian Peace Medal

- reverse |

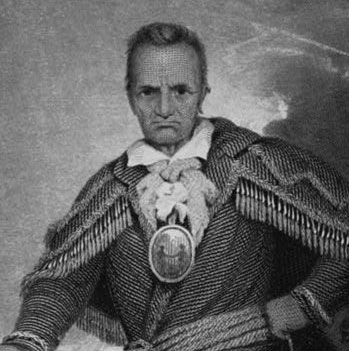

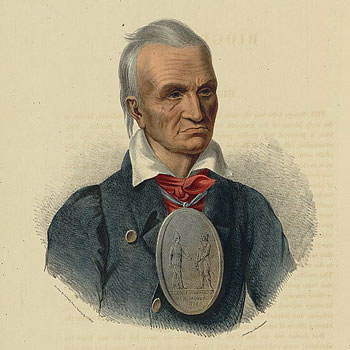

These two images shows Sa-go-ye-wat-ha [Seneca chief Red Jacket]

wearing the Washington Indian Peace Medal.

|

|

Sa-go-ye-wat-ha [Seneca chief Red Jacket]

/ painted by R.W. Weir ; eng'd. by M.J. Danforth, Prints

and Photographs Division, Library of Congress |

Red Jacket. Seneca

war chief / on stone by Corbould from a painting

by C.B. King ; printed

by C. Hallmandel,

print, Philadelphia : Campbell & Burns,

ca. 1835. Prints and Photographs

Division, Library of Congress

|

Resources:

Back

to Top

Acculturation

Educating the Indians : a female pupil

of the Government School at Carlisle visits her home

at Pine Ridge Agency. Frank Leslie's Illust. Newspaper,

Mar 15, 1884, cover. Prints and Photographs Division,

Library of Congress.

Educating the Indians : a female pupil

of the Government School at Carlisle visits her home

at Pine Ridge Agency. Frank Leslie's Illust. Newspaper,

Mar 15, 1884, cover. Prints and Photographs Division,

Library of Congress. |

Indian Schools

In the late 1800s, the United States supported an educational

experiment that the government hoped would change the

traditions and customs of Native Americans. Special

boarding schools were created in locations all over

the United States with the purpose of "civilizing"

American Indian youth.

Thousands of Native American children were sent far

from their homes to live in these schools and learn

the ways of white culture. Many struggled with loneliness

and fear away from their tribal homes and familiar customs.

Some lost their lives to the influenza, tuberculosis,

and measles outbreaks that spread quickly through the

schools. Others thrived despite the hardships, formed

lifelong friendships, and preserved their Indian identities.

Read more:

The Challenges and Limitations of Assimilation

The Brown Quarterly, Vol. 4, no. 3 (Fall 2001)

http://brownvboard.org/brwnqurt/04-3/04-3a.htm

|

Explore a lesson plan from the Library

of Congress about these schools:

Indian Boarding Schools: Civilizing the Native

Spirit.

This lesson plan uses photographs, letters, reports,

interviews, and other primary documents to help students

explore the forced acculturation of American Indians

through government-run boarding schools.

http://memory.loc.gov/learn/lessons/01/indian/overview.html

Websites for Indian Boarding Schools:

|

Back

to Top

Indian

Removal Policy

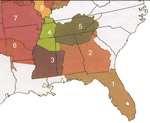

Questions for Indian

Tribes Map Questions for Indian

Tribes Map

1. Even after ceding, or yielding, millions of acres of

their territory through a succession of treaties with the

British

and then the U.S. government, the Cherokees in the 1820s

still occupied parts of the homelands they had lived

in for hundreds of years. What modern states are included

within the boundaries of the Cherokee Nation? How large

is the territory compared with the modern states?

2. What other tribes lived near the Cherokees? Whites

often referred to the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek,

and

Seminole as the "Five Civilized Tribes." What do

you think whites meant by "civilized?"

Visual

Resources:

The following maps illustrate the land holdings of the Cherokee

people at specific times in history:

|

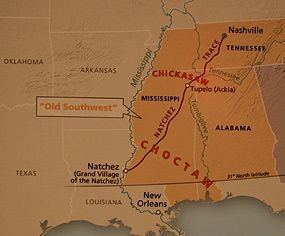

Before the United States

expanded beyond the Mississippi River, the land that

would become Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee was

known as the Southwest.

This map shows the Old Natchez

Trace passing through Choctaw and Chickasaw lands. The

440-mile-long path extends from Natchez, Mississippi

to Nashville,

Tennessee, and linked the Cumberland, the Tennessee

and Mississippi rivers. The word "trace" is

an old French word which meant a line of footprints

or animal tracks.

What effect did this travel route have

on the Indian life and culture? |

National Park Service

Image

|

|

Back

to Top

Resistance

to Indian Removal

Resources for more information about women's petitions:

- Their Right to Speak: Women's Activism in the Indian

and Slave Debates By Alisse Portnoy, 2005, Harvard

University Press.

- Alisse Theodore [Portnoy], “‘A Right to Speak on the Subject’:

The U.S. Women’s Antiremoval Petition Campaign, 1829-1831,”

Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 5 (2002), 601-24.

This section from: http://expostfacto.historytools.org/womens-petitions-against-indian-removal/

In late 1829, Catherine Beecher anonymously published a circular

letter addressed to the “Benevolent Ladies” of the United

States.

Catherine Beecher, “Circular Addressed to the Benevolent

Ladies of the U. States,” Dec. 25, 1829, in Theda Purdue

and Michael D. Green, eds., The Cherokee Removal: A

Brief History with Documents, 2nd ed. (Boston: Bedford/St.

Martin’s, 2005), 111-14.

In this letter, Beecher sympathetically portrayed the “poor

Indian[s]” as a dignified people, no longer “naked and wandering

savages,” who had made much progress towards becoming Christian

and civilized. Although Beecher showed little interest in

the native cultures of the Indians of the South, her remarks

showed no sign of racism (as distinct from ethnocentrism).

Instead, she focused on the fact that the U.S. government

had promised to protect these Indians and their lands. (The

Indian nations in question included the Cherokee, Chocktaw,

Creek, Seminole, and Chickasaw, which were often collectively

referred to as the “Five Civilized Tribes” because of their

notable adaptation to white, American ways.) Beecher was writing,

she declared, because “it has become almost a certainty that

these people are to have their lands torn from them, and to

be driven into western wilds and to final annihilation, unless

the feelings of a humane and Christian nation shall be aroused

to prevent the unhallowed sacrifice.” Clearly, Beecher did

not believe the rhetoric of the Jackson administration that

removal would be voluntary and that it was necessary to protect

Indians — instead, she said, Indians’s land would be “torn”

from them, and their removal west would lead to their “annihilation.”

In short, Beecher thought that she saw through the pro-removal

rhetoric to the real reason that Indians were to move west

— their “fertile and valuable” lands were “demanded by the

whites as their own possessions.”

This letter helped inspire a small but significant petition

campaign on the part of American women. Alisse Portnoy has

carefully studied this petition campaign. While her article

helps document the political resistance to the Indian removal

policy, it also shows how women in the early republic period

began tentatively to assert a “right to speak” regarding political

issues. Portnoy shows that how these women spoke is just as

important as the fact that they did so.

Here are several questions to consider when reading this

essay:

- What main arguments does Portnoy make?

- What evidence does she bring forward? Where did she get

this evidence?

- Where did the petitions come from? What might be the significance

of their regional source?

- Why are these petitions historically significant?

- Why weren’t the petitions effective in changing Indian

policy?

Back

to Top

The

Human Meaning of Indian Removal

What went wrong on the Trail of Tears? Ask students

to compare Scott's letter and general order, statements about

what should have happened, with Burnett's narrative of what

he saw. Since soldiers did not, routinely ignore

general orders, the vast discrepancy between these primary

sources calls

Scott's sincerity into serious question. The fact that the

army did not investigate what happened also suggests that

the general order was never supposed to be taken literally.

Questions

for Trail of Tears Map Questions

for Trail of Tears Map

1. How many different routes are shown? Why do you think

there might have been so many?

2. Find the water route. What rivers does it follow? What

advantages to you think it might have over an overland route?

What difficulties might it present?

3. Locate the land route. How does it compare with the other

main routes? What major rivers did it cross? What advantages

and what disadvantages might the Land Route have?

4. The largest group of Cherokees followed the land route.

They left Tennessee in the late fall of 1838 and arrived

in Indian Territory in March. What problems do you think

they might have encountered on the journey?

Resources:

Back

to Top

Lesson

Plans

Primary

grades:

- Traditions

and Languages of Three Native Cultures: Tlingit, Lakota,

& Cherokee

This lesson compares the cultures and languages of the

Tlingit, Lakota, and Cherokee American Indian tribes, and

helps students learn the importance of preserving a group's

traditions.

http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id=378

- Native American Cultures Across the U.S.

This lesson discusses the differences between common

representations of Native Americans within the U.S. and

a more differentiated view of historical and contemporary

cultures of five American Indian tribes living in different

geographical areas. Students will learn about customs and

traditions such as housing, agriculture, and ceremonial

dress for the Tlingit, Dinè, Lakota, Muscogee, and

Iroquois peoples.

http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id=347

Middle grades:

- Not 'Indians,' Many Tribes: Native American Diversity

Students study the interaction between environment and

culture as they learn about three vastly different Native

groups in a game-like activity that uses vintage photographs,

traditional stories, photos of artifacts, and recipes.

http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id=324

- Anishinabe - Ojibwe - Chippewa: Culture of an Indian Nation

This lesson focuses on one American Indian Nation, the

Anishinabe, also known as the Ojibwe, Ojibway, or Chippewa

Indians. Students will learn how to conduct a research project

on different historical, geographical, and cultural aspects

of this Native American group.

http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id=369

- Native American policy

The lesson supports students' examination of the different

views and policies about native americans from 1787 through

1830.

http://www.historynow.org/09_2006/lp3.html

Secondary grades:

|