The Changing Character of Immigration

by

Kate Holladay Claghorn

Scanned from World's Work, Vol. 1, 1900-01

NEARLY half a million immigrants came to our shores during the year that ended June 30, 1900, the statistics of which have just been published. This is the largest number that has come since 1893. A curve showing the fluctuations of immigration since 1875 would rise rapidly after the low point of 1878 to more than three-quarters of a million in 1882 and sink again in 1886 to a third of a million, again rise to the highest point since then in 1892, and then rapidly decline till 1898

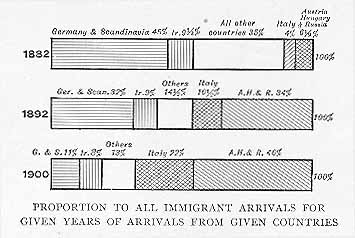

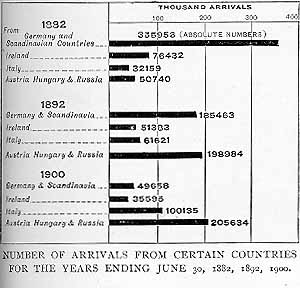

While these figures show nothing surprising as a total, an interesting change has taken place in the proportions of nationalities that come to us. Compare this year with two previous years of large immigration—1882 and 1892 (which are the crests of the two highest waves), in respect to arrivals from Germany and the Scandinavian countries, regarded as one group, from Austria-Hungary and Russia, regarded as another group, from Ireland, and from Italy. German and Irish immigration has shrunk, and Italian has greatly increased.

It is noteworthy that the Austro-Russian group and the German-Scandinavian group have changed places as extremes since 1882. Last year, arrivals from Italy go beyond any previous record, with a total of over a hundred thousand, about double the arrivals from Germany and Scandinavia together, double the arrivals from Ireland in 1892, and one-third more than the Irish arrivals in 1882.

The change in the composition of our immigration is made even more plain by reducing the different national elements to percentages of the total immigration in each year considered, as is shown in the diagram of immigrants from given countries.

The decreasing elements have been grouped at one side of the table, the increasing elements at the other, in shaded blocks, the unshaded blocks between the shaded blocks representing all other elements in the total of immigration for each year.

The statistics of immigration for successive years would be even more significant, however, if the present system of classifying arrivals according to race as well as to country of residence, had been adopted sooner. The student of social matters has to thank Mr. Edward F. McSweeney, the present Assistant Commissioner of Immigration at the Port of New York, for the introduction of this better system of classification, the first results from which are given in the reports of immigration for the year ending June 30, 1899.

It is now possible to disengage the significant racial facts. For example, we can tell from last year's figures that of the 90,787 arrivals from the Russian Empire, 12,515 were Finns, 37,011 were Hebrews, 32,797 were Lithuanians and Poles, and only 1165 were "Russians" proper.

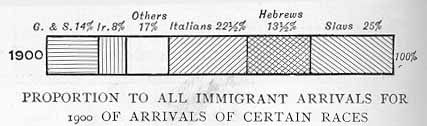

Moreover, arrivals of the same race element from different countries may be grouped together. For instance, after grouping together all Germans by race, while arrivals from the German Empire in 1900 were 18,507, arrivals from all countries of persons of German race were 29,682. Hebrew arrivals for the year were 60,764. Arranging these figures by percentages of the total immigration in a bar makes the matter plainer to the eye.

The noticeable feature in recent immigration is the predominance of three racial stocks, usually considered of doubtful social and industrial value,—the Slavs, the Italians, and the Hebrews. Our problem now is the problem of the Italian, the Jew, and Slav—no longer of the Irishman and the German.

If we look at the human tide as it first washes our shores at the immigrant station, we shall see patient family groups—father, mother, and little children, old grandfather and grandmother, perhaps, and sturdy grown sons and daughters—as they sit beside their little possessions awaiting with eagerness the moment of their exit to a land of freedom and opportunity. The girls and women who pass the gate alone are moral and industrious peasants in the main—wives coming to husbands, sisters to brothers, or they are making the venture on their own responsibility. Even the bands of unattached men are not so bad as fancy paints them. Tall, ferocious-looking Croats and Slovacks are found, upon acquaintance with them under normal conditions, to be simple country fellows, ready to talk and sing, or to drink sociably, ready to work at anything that offers itself, planning to save the greater part of their earnings for wives and children left behind. Weather-beaten Italians, with seamed and lowering countenances, are meditating nothing darker than their chances of slipping by the inspector and gaining their foothold in the promised land.

We have practically no immigration from city slums, and very little from city populations of any sort, except the Russian Jewish immigrants, whose circumstances are peculiar, and who cannot be said, as a people, to have become infected with the characteristic slum vices. Our immigrants as a whole are a peasant population, used to the open, with the simple habits of life, the crude physical and moral health that the open air and poverty together are apt to produce. Practically all the immigration from Austria-Hungary, which has grown so considerably of late years, is from the country, as is also the immigration from Italy. The Italian mendicant, who is seldom seen here, is a member of a highly specialized class, and is as unwilling to leave his city haunts as any other specialized and privileged social product of his country would be.

In the immigrant group as a whole arc to be found poverty, ignorance, weakness, a pathetic patience, a no less pathetic hopefulness of what the future will bring, a childlike ingenuity of deceit in eluding the pains and penalties of detention and exclusion; but so little full-fledged and out-breaking viciousness that it is not worth talking about. In short, like the other class of beginners in citizenship they come to us as little children, and claim our care and protection as such.

But what course of training in citizenship is prepared for these grown-up children? A large proportion of them, for one reason and another, find their first homes in the slums of great cities. And so it unfortunately happens that, just as poverty and vice, ignorance and depravity, are confused together in our thought about them, so in our cities the newest immigrants who are the most hopeful element in our slums, are brought in direct relation with the vicious and defective remnant left behind by earlier comers. The man who is climbing up the ladder stands, while still on the lowest round, with the man who has slipped down there from a higher place, or who has stood there forever.

When the two sets of elements—the poor and the corrupt—come in contact, some mutual impression must be made. It has to be acknowledged that in some cases the incoming of newer peoples has had a distinctly beneficial effect in the neighborhoods they have taken possession of. In New York, for example, the old Fourth and Eleventh wards, long the haunt of the drunken sailor and his vicious mate, have been to a large degree cleaned up by the incoming of Greeks, Italians, and Russian Jews. Ground-floor tenements formerly occupied by saloons and dance halls are now the lodging places of Greek pedlers, who live together in peace, quiet, and order, smoking and playing cards at home on a rainy day, neither drinking nor fighting, well thought of by that great power in tenement-house life—the " housekeeper "—and by neighboring families. Above stairs newly arrived Italians, industrious and of sober habits, have driven out the drunken Irish pauper of the second generation, to the great satisfaction of the charitable agencies that have had to struggle for so many years with the latter class.

On the other hand, there are influences of tremendous force constantly at work to drag the newer immigrants down. Especially bad is the tenement house for the newly arrived immigrant. The robust physical health of the peasant fails in the poisonous air of his dwelling; such habits of cleanliness, order, and decency as the immigrant family may have brought with it are in serious danger of wreck in unsanitary and crowded quarters. Not knowing localities and prices, the immigrant takes up his abode in the parts of the city nearest his point of entry, which is, in New York, the most expensive part of the city, so far as rents are concerned. A family must not merely confine itself within as narrow limits as possible, but must, in order to meet the expense, ask another family to share the space already too narrow for itself. The moral as well as the physical evil that such crowding brings does not need to be described.

It is, perhaps, a fortunate rather than an unfortunate circumstance that as families of the newer races crowd into a given tenement, earlier comers move out. The "colony," composed of one sort of foreigners solely, representing approximately the same period of immigration, has this favorable feature, at least—it is made up of elements of similar kind. The old stager in vice and trickery is not so likely to be at hand to instruct the inexperienced new arrival in all branches of his art, nor the practiced pauper, to give the dangerous lesson of dependence to the normally self-helpful immigrant.

All evils, however, are favored by an institution which is the greatest evil of them all,—that is, the peculiar system of political control under which our great cities groan, "politics for profit," an organized business, run primarily for the advantage of its managers, secondarily for the benefit of their sub-agents.

The tenement house itself, with all its evils involved was here when the immigrant came; but the continuation of the worst features of the tenement in spite of laws enacted for its improvement, is the direct result of "politics for profit." Requirements with regard to round space to be occupied, to the size and character of air-shafts, to other matters of constriction when the building is to be erected, requirements for the lighting of hallways, to proper sanitation, to the character of inmates, after the tenement is built, are violated with impunity.

The immigrant problem is a very serious one; but we succeed with it directly in proportion to our skill or neglect in dealing with it. The material is, in the main, good raw material for American citizenship.

There has never been a sufficiently careful oversight of fresh

immigrants in our crowded cities; for they ought to be regarded as civic

children and cared for as such. But somehow, in haphazard ways, we assimilate

them—developing the best traits in most of them but not in all, taking our

chances. They take their chances, too, in coming; and the wonder is that we both

survive the experiment as well as we do. The children of almost any kind of

parents become American.

This page was created by Patrick J. Hall.